In this issue

NOT all in this together : The Government’s “tough but fair” budget will hit the poorest the hardest, as well as having a disproportionate impact on women. Meanwhile, the Sunday Times Richlist reveals that the richest 1,000 people in Britain added 30% to their wealth despite the recession.

Is this farewell, welfare?: The government’s answer to the problem of unemployment during the biggest economic crisis since the 1930s is not to create any new jobs, but to launch a massive attack on our living standards.

China: trouble in the world's sweatshop: China is experiencing a rising wave of industrial unrest, as workers increasingly turn to collective action to fight against their exploitation.

Academy schools programme expanded A new Education Bill is set to massively extend Labour’s controversial Academies programme.

Strikes off, cuts on at universities: Industrial action at Sussex university has been called off.

China: trouble in the world's sweatshop

China is experiencing a rising wave of industrial unrest, as workers increasingly turn to collective action to fight against their exploitation.

Rapid industrialisation over the past few decades has created massive internal migration from the countryside to the cities on an unprecedented scale, dwarfing Britain’s industrial revolution two centuries ago. Now, this new urban working class has begun to flex its muscles, disrupting production in order to assert their demands.

The high-profile suicides at Foxconn, who make iPhones for Apple, were merely the tip of the iceberg. There, angry workers rioted over sweatshop conditions, chanting “capitalists kill people” and brandishing pictures of the CEO of Foxconn, Terry Gou. The company quickly offered improved wages and conditions in an attempt to quell the storm. However these headline-grabbing measures were quickly eaten up by reductions in overtime and speed-ups on production lines.

Elsewhere, 1,000 workers at the Denso car parts plant in the southern province of Guangdong won a two-day strike over poor breakfasts. China’s factories are vast – some the size of whole cities. Some employ tens of thousands of workers at a single site. Coupled with long working hours, this means workers often don’t leave work to eat meals, and the quality of those meals has proved a flashpoint. Workers ignored the pleas of the official union to return to work, and forced company bosses to improve meal provision.

For nearly three decades, corporations have increasingly relocated manufacturing to China to take advantage of a vast supply of cheap labour and lax regulation. The consequences of that lax regulation have also provoked social conflicts. 1,000 villagers in Jingxi county, Guangxi province, near the border with Vietnam recently protested against pollution from an aluminium plant owned by one of the country’s largest aluminium producers. Villagers blocked the gates to the plant and damaged production facilities, and one local government official was taken to hospital after being hit by stones.

In the past two months workers have walked out at three Honda plants, a Toyota supplier, a Hyundai factory in Beijing, a rubber products manufacturer in Shanghai and a Carlsberg brewery. Recently, workers at Japanese electronics firm Tianjin Mitsumi crippled output with a sit-in, complaining they were being asked to work extra hours for no extra pay.

The rising assertiveness of Chinese workers is causing some corporate investors to look elsewhere. However, industrial unrest is a pattern repeated across the region. In Cambodia, workers staged a three-day strike in July in a dispute over the minimum wage, while in Vietnam thousands of workers at a shoe factory staged a strike demanding higher salaries. While wages in Vietnam and Cambodia are still a fraction of those won by Chinese workers, increasing militancy is rapidly closing the gap.

Beverly Silver is a Professor of Sociology at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and an expert on workers and globalisation. She is not surprised by the latest developments, stating that “corporations have been chasing the mirage of cheap and disciplined labour around the world, only to find themselves continuously recreating new militant labour movements in the new locations.”

Is this farewell, welfare?

The government’s answer to the problem of unemployment during the biggest economic crisis since the 1930s is not to create any new jobs, but to launch a massive attack on our living standards.

In the emergency budget, one group of people who will be hit the hardest is welfare claimants.

Benefits are not just for the unemployed. They supplement low pay and give those with disabilities or caring responsibilities a means by which to survive, as well as providing income to those who cannot find unemployment. With around 2.5 million people claiming Job Seekers Allowance (JSA), 2.9 million receiving Disability Living Allowance (DLA), around 5 million reeceiving working tax credits and further claimants on other tax credit schemes and Employment and Support Allowance (ESA), more than one-in-three of Britain’s 30 million strong workforce are receiving some form of state welfare.

But welfare also traps people in poverty. Both housing benefit and tax credits, for example, are a massive subsidy to employers and landlords. On the surface they help people on low incomes to afford housing and to keep their household running, but they also allow landlords to charge higher rents and the employers to pay lower wages, both making more profit in the process.

Meanwhile, those claiming the benefits remain on the breadline, and working more in fact leaves them with less money. For example, working more than 16 hours counts as being ‘in work’ for JSA, but you need to work 30 hours to claim Working Tax Credits. Working more can mean earning less as your benefits are reduced faster than your income rises.

In order to get around this, people often turn to the black economy. You don’t pay tax on cash-in-hand jobs and it doesn’t affect your benefits. Hence, there are more people working in domestic service than in Edwardian times, and single parents in particular are amongst those often forced to work “illegally.”

For its part, the state is happy with this situation as it drives down wages overall, keeping the labour market ‘competitive’ and ‘flexible’. It also gives them a stick to beat the poor with; the fact that their policies have forced so many people onto the black economy making their propaganda about benefit “cheats” a much easier sell to those workers who don’t claim welfare.

Indeed, benefits ‘fraud’ accounts for around £3 billion a year, while estimates put the amount of benefits left unclaimed at between £4bn and £8bn. In other words, if all ‘fraud’ stopped, but everyone eligible for benefits received them, the government would be worse off. Dwarfing these figures, the total gap of uncollected taxes, mostly from the wealthy employing methods of tax avoidance and evasion is £120 billion. However, pound-for-pound the government spends 624 times more on adverts demonising ‘benefits cheats’ than rich tax dodgers – a sure sign that their priority is propaganda and not a genuine desire to balance the books.

The fact that so many people are forced to work “illegally” in order to survive is not an indictment of them, or of the idea of social welfare. It is an indictment of the capitalist system in which the state engineers just this situation in order to inflate private profit.

This is the context of the so-called ‘welfare reforms’, which are aimed at making the unemployed, single parents, the sick and the disabled compete for scarce and badly paid jobs on the labour market, in order to push a ‘flexible’, insecure, low-wage economy. This regime is not in the interest of those who are in work. At a time when employers, under the pressure of the crisis are attempting to make us work harder for less money, these ‘welfare reforms’ aim to force those who don’t have a job to accept even worse wages and conditions.

The emergency budget outlines plans to cut £11 billion from the welfare budget. One big cut comes from linking all benefits apart from the state pension to the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) measure of inflation rather than the Retail Prices Index (RPI) one. CPI is typically lower as it excludes housing costs. Over the past 20 years it has been higher than the RPI on just three occasions. The August CPI is 3.4% while the RPI is 5.1%.

Since inflation is the measure of rising prices, by pegging benefits to the lower measure the government is ensuring benefits will fail to keep up with the cost of living – effectively cutting benefits year-on-year. And this doesn’t capture the whole picture. According to the BBC Economics Editor Stephanie Flanders, “Research has tended to show that the cost of the basket of goods bought by poorer households often rises faster than the basket of goods included in the CPI.” That means that the year-on-year cut to benefits is even greater than the headline figures suggest.

There is also an increasing drive to turn welfare into workfare (see ‘hello workfare’ bellow), where private companies pocket public cash to link benefits to compulsory work placements. For a standard 40-hour week this can mean working for just £1.60,/hour less than a third of the minimum wage. This doesn’t create jobs, it just undermines the wages of those still in work.

The criteria for ‘the sick’, Employment and Support Allowance or ESA, are also being tightened up (see below). This has already led to tragedy, with one person in Scotland suffering from severe depression committing suicide after being forced back to work. Tax Credits for middle-income families will also be cut back, deepening the poverty trap as low income workers who do manage to earn more will simply have it taken away again through reduced tax credits.

The upshot is that the situation for claimants looks bleak. However, they are not all taking it lying down. The ‘no to welfare abolition’ network (defendwelfare.org) is “a grassroots network to extend and defend welfare rights”, incorporating local claimants groups who have been picketing agencies involved in the Flexible New Deal as well as offering support to striking job centre workers. Claimants, like the wider working class certainly have a fight on their hands to defend their living standards.

Fixing the sick - welfare reform style

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) is the sickness benefit introduced in October 2008, which will eventually replace Incapacity Benefit. Its new test is extremely difficult to pass and almost nobody is exempted from the test.

A serious problem for sickness claimants today is that their medical assessment is made through the use of a computer program, the ‘Logic Integrated Medical Assessment’ (LiMA). This programme was introduced by DWP’s contractor Atos Origin in 2005 to assess claimants for the old sickness benefit (Incapacity Benefit). Already in December 2005, advice charity Child Poverty Action Group complained of serious problems with Atos’s computer-aided medical assessments in an article entitled ‘The computer says no’.

During the examination, the doctor asks the claimant a list of questions, which the computer shows on the screen. While the claimant speaks, the doctor builds, through the use of a windows system and drop-down menus, a combination of words and numbers which resembles what the claimant says.

The result is an often surreal computer-generated ‘Medical Report’, based on a collection of mechanically-constructed brief sentences. More than one Social Security judge has noticed with alarm that automated reports did not reflect what the claimants had actually said and contained ‘nonsensical statements’.

After aiding the doctor to construct brief phrases, the computer automatically derives implications from these phrases. These implications are often overstretched, or even totally wrong, and options for investigation of these implications are blocked by the computer system. For example, if a claimant cannot cook but tells the doctor that he makes himself snacks or tea, this ‘ability’ is used by the computer as ‘evidence’ of a very large range of physical and mental capacities.

Furthermore, the handbook for Atos’s doctors tells them to apply the harshest possible interpretation to the test. For example, the handbook says that if a claimant’s memory is not so bad that he forgets to get dressed in the morning, he cannot really score anything at all for memory problems.

Many sick people, although unable to work, do wish to attend courses, and they don’t because they are afraid of losing their benefit. Any mention of having done any activity whatsoever will be used to disqualify a claimant from his sickness benefit. An extreme example from the Citizens Advice Bureau: a claimant was found ‘fit to work’ because he attended a compulsory ‘Work Focused Interview’! The automated medical report said: ‘the client is actively seeking work through Jobcentre Plus’ .

The ‘Brighton Benefits Campaign’ has been fighting for claimants and low waged workers since the recession began. They say that “a fight for a more humane medical assessment is also a fight for the abolition of Atos’ mechanised methods – for the dismissal of Atos and the return to a professional medical service, publicly run, and run not for profits.” The antagonism between private profit and claimants’ needs only looks set to deepen as the welfare cuts begin to bite.

Hello workfare

One of the latest reforms is the introduction of the ‘Flexible New Deal’, which began in October 2009. The year-long scheme is not run directly by the government, but is contracted out to a number of private companies who stand to receive millions in public money to bully the unemployed into accepting any job at rock bottom wages. This won’t create any new jobs – it will just force the unemployed to compete desperately with each other for the few jobs that are available. The effect of this on the labour market will be to push down wages and reduce job security even further.

After six months on the FND claimants are forced to work for their benefits (workfare) for one month: 40 hours work a week for 4 weeks in order to receive a meagre £64.30 a week (or even less for couples or the under 25s). Even for those on the ‘higher’ rate, this is just £1.60 an hour! The scheme benefits employers and nobody else. Why take on workers at minimum wage or higher when you can get them at £1.60 an hour? Those who lose their jobs due to the recession may one day find themselves forced to work their old job for benefit levels. This will only exacerbate the ‘race to the bottom’ in wages and conditions which is fast becoming the norm in the ‘modern economy’.

Academy schools programme expanded

A new Education Bill is set to massively extend Labour’s controversial Academies programme.

The Education Secretary Michael Gove has now added Ofsted-graded “outstanding” schools to the hit-list. His plans promise even more Academies; over 150 schools have already applied for Academy status, with hundreds more enquiring for further information or registering an interest. The Academies scheme allows non-state bodies, including religious groups, businesses and voluntary groups to take control of schools in exchange for a nominal amount of funding for new facilities.

Academies were the previous government’s answer to perceived “low standards” in too many secondary schools, even though the whole idea of standards did not take into account the social backgrounds of the students going to the schools – problems created not by schools themselves but government policies and wider social problems. Under the scheme a private sponsor can take over a state school and be given control of the entire budget direct from the government. They are able to influence admissions criteria – taking the brightest students from other local schools - and appoint the governing body – which is meant to be a voice for local stakeholders.

The measures are being billed as giving more ‘freedom’ to schools. But the National Union of Teachers (NUT) comments that “these ‘freedoms’ are however a mask for a structural shift in who controls schools (…) Billions of pounds of assets in the form of school land and buildings will be transferred to Academy proprietors.” Wealthy individuals and partisan groups taking over schools have also had a notorious effect on prejudicing teaching. For example a whistle-blowing teacher was awarded £70,000 for unfair dismissal against the King Fahad Academy in Acton. He had refused to use books likening Jews and Christians to “monkeys” and “pigs”. While the school is fee-paying, the Academies system stresses such groups are allowed autonomy for their religious projects.

The scheme is also ripe for cronyism. For example Brighton & Hove’s Falmer School is to be reopened in September as the Aldridge Community Academy after local “entrepreneur” Rod Aldridge. Aldridge’s background has been in making millions out of government IT contracts as the head of Capita Business Services. Naturally, getting rich from successful bids for funding - after secretly lending the Labour Party £1m - is not the same as running a complex institution like a school.

Despite there being no requirement for private sponsors to have any expertise, let alone experience, in education they will have the power to decide on the curriculum in most subjects. Academies can also set their own terms and conditions for staff new to the school. Although they often promise to keep to national pay scales, once the budget crisis hits them, this will be a likely area to cut. The NUT has warned that “there could be a free for all in terms of pay and conditions and a greater role for bullying head teachers.”

As of August 2010, 34 schools had already begun TUPE consultations – the legal process for transferring terms and conditions of staff over to a new employer, in this case the Academy. While TUPE legislation protects the terms and conditions of existing staff, it offers no such protection to new employees. This often results in the creation of a two-tier workforce, with new staff on inferior conditions gradually replacing the previous workforce.

Catalyst spoke to a high school English teacher who said such measures will “create division in the workforce, lower morale and raise staff turnover – all things that harm the continuity of young people’s educational experience. All this haste to increase the number of Academies begins to feel like a bad idea, when you consider that there has been little or no research into the impact of this programme on the effectiveness of schools. Academies put resources into private hands and create a two-tier ‘public’ education system.”

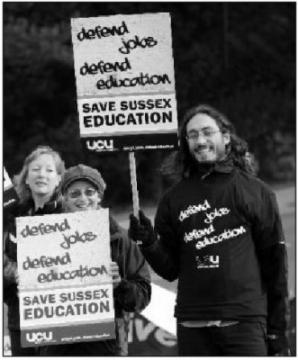

Strikes off, cuts on at universities

The academics’ union UCU at the University of Sussex cancelled industrial action planned for late June after university bosses declared they were “hopeful” they could avoid any compulsory redundancies.

It soon emerged however that compulsory redundancies had been transformed into ‘voluntary’ ones and the number of job losses remained at over 100, with a similarly severe impact on many courses and workloads expected.

One student mocked the management statement: “We are pleased to announce that the 100 have jumped, and were not pushed. The knives to their backs were unrelated.” A lecturer also commented that “I, among many, have been made ‘voluntarily’ redundant, after being selected for compulsory redundancy. The University seems to have got rid of everyone it wanted by forcing us to accept a ‘voluntary’ settlement.”

The other unions at Sussex, Unite and Unison, representing support staff such as porters, cleaners, IT and workshop technicians, did not even enter in dispute with the University. But like UCU, both Unite and Unison aimed at reducing compulsory redundancies and improving voluntary redundancy packages.

Whilst committee members continued the consultation process, some of the rank and file members argued that the starting point of the unions was wrong, and they should be opposing cuts altogether. None of the three campus unions had rejected university bosses’ line that savings needed to come from staff costs - despite ongoing multi-million pound building projects, and the Vice-Chancellor behind the cuts granting himself a 43% pay increase to £227,000 a year.

“Our area rep came to a special Unite meeting, arguing to give them two more weeks consultation with management,” said Tony, a Unite member and IT worker. “If there was no significant movement during this time, the area rep said she would bring the ballot papers to the next meeting. It shouldn’t be too much of a surprise that she didn’t even turn up to the next meeting, let alone bring ballot papers!”

Frustrated with their union’s unwillingness to fight, a group of workers set up the Support Staff Forum (SSF), involving workers from all three campus unions, non-unionised workers as well as several students. Paul, a worker involved in the group, said “one of the good things we have been doing is making both us in the SSF and the wider campus community aware of the cuts and changes in working conditions in the different sectors, as although we all work on the same campus each department can be quite insular.” The SSF also had some success in building solidarity among education workers, such as by encouraging non-UCU members to honour UCU picket lines.

Despite several strike days, widespread support and solidarity, and a vibrant student campaign leading to a week-long occupation in which many hundreds of students and education workers took part, the UCU’s suspension of industrial action marks the end of the dispute. As one would-be striker commented, “Though UCU exec worked tirelessly to achieve the best outcome possible, I feel that once they accepted the need for cuts, they could only negotiate a defeat. Higher Education bosses are using the budget crisis to push through long-term restructuring that will destroy education as we know it. So instead of focusing only on compulsory redundancies, we should have stopped them wrecking our university by opposing all staff reduction. However it looks like UCU nationally are more interested in being involved in restructuring than in stopping it.”

UCU held a ballot for an academic boycott against Sussex, demanding an Avoidance of Redundancy committee which Sussex bosses had rejected out of hand. Earlier in the year at Leeds University UCU had called off industrial action against 700 redundancies after reaching a “groundbreaking” settlement that included setting up an all-union redundancy avoidance committee and postponing any compulsory redundancies until completion of a review in January 2011. However, it later emerged that 400 staff had volunteered for redundancy. With large cuts to higher education budgets, UCU estimates that 22,500 redundancies are in the pipeline in higher education, on top of 34,000 job losses in further education.

NOT all in this together

The Government’s “tough but fair” budget will hit the poorest the hardest, as well as having a disproportionate impact on women, two reports have found.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) describes the budget as signalling the “longest, deepest, sustained period of cuts to public services spending at least since WWII”. Chancellor George Osborne claims austerity is “unavoidable” in order to reduce Britain’s deficit, and business leaders have sounded their approval for the plans. However, trade unions warned of hundreds of thousands of job losses, accusing the government of “declaring war on public services”.

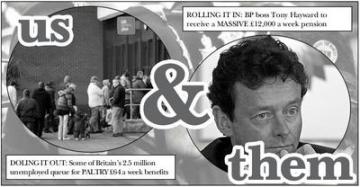

Meanwhile, the Sunday Times Richlist reveals that the richest 1,000 people in Britain added 30% to their wealth despite the recession. Now a new report has rubbished the claim that the budget is “fair”. ‘Don’t forget the spending cuts’, commissioned by the Trade Union Congress and the public sector union Unison, looked at the impact of the budget on different income groups. Because for example, richer people can afford private alternatives they are less reliant on public services. Likewise, the less well off people are, the more likely they are to be receiving benefits. The report modelled this and found that cuts to public services and welfare are likely to disproportionately impact the less well off.

The authors write that “The impact of these cuts will be deeply regressive. All households are hit considerably, but the poorest households are hit the hardest.” Specifically, they found that “the average annual cut in public spending on the poorest tenth of households is £1,344, equivalent to 20.5% of their household income, whereas the average annual cut in public spending on the richest tenth of households is £1,135, equivalent to just 1.6% of their household income.”

This finding was echoed by IFS director Robert Chote, who explained the cuts “are likely to hit poorer households significantly harder than richer households”. Particularly he cited the decision to link benefits payments to the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) rather than the Retail Prices Index (RPI). CPI is typically lower than RPI (which includes housing costs), which means the cuts will become cumulatively worse in real terms for benefits recipients, as prices rise faster than their benefits payments.

Separately, the Fawcett Society has launched a legal challenge to the budget, describing it as “blatantly unfair”. They claim that of £8bn cuts, £5.8bn will affect women, and are seeking a judicial review in the High Court, claiming the government failed to carry out an equality assessment when deciding the austerity measures. Fawcett Society solicitor Samantha Mangwana stated that “George Osborne expects women to pay three times more than men to accelerate deficit cuts, even though women still earn and own far less.”

The headline measures in the budget is an unprecedented £113bn cut budget squeeze by 2014-15. This will involve 25% cuts to virtually all government departments (with some protection for the NHS and International Development), £8bn from net tax rises (mostly from VAT increasing to 20%)and £11bn in welfare cuts (see our special feature on the left of this page). On a closer look, it becomes clear just how regressive these measures are. While corporate taxes have been reduced, VAT – a regressive tax – has been increased. As already noted, benefits and public service cuts also disproportionately impact the less well off. Effectively this is a budget to punish ordinary workers for an economic crisis we were not responsible for.

Major banks have already returned to profit. Northern Rock, RBS and Lloyds banking group, all saved by state bailouts, announced they had returned to profit in July 2010. HSBC also recently announced its profits had doubled to £7bn for the first 6 months of 2010. The return of 6-figure bankers bonuses has also been widely reported. Elsewhere in the corporate world, the recession is also already a thing of the past. BP Chief Executive Tony Haywood will collect a massive £600,000-a-year pension when he retires in October, despite taking much criticism for his role in the Gulf of Mexico oil spill.

So are the austerity measures really “unavoidable”? That depends on your point of view. For the politicians, bankers and business leaders, absolutely. The £850bn bank bailout that prevented the financial crisis turning into an all-out capitalist collapse dwarfs the savings from austerity. But having staved off collapse, the masters of the economy find themselves between a rock and a hard place, and as ever their solution is to give us a good squeeze in their place.

Their dilemma is this: cut too much, and consumer spending will inevitably fall, raising fears of a ‘double-dip’ recession. A double-dip recession would be bad for the economy and bad for corporate profits, and would probably lead to yet more cuts to public services, jobs, wages and benefits. But cut too little, and the cost of the recession will be borne by businesses and the rich. That too is bad news for them, for obvious reasons. Essentially they are gambling that they can cut our incomes without much knock-on effect on our spending.

If that doesn’t make much sense, that’s because it really is a gamble. The ‘boom’ was sustained by cheap credit. Wages failed to keep up with rising prices, but the combination of rising house prices and easy credit meant consumer spending could grow and grow. But it was always a bubble, one that burst spectacularly when the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the US sent shockwaves around the world’s financial system. Collapse was only averted by massive bailouts. So a repeat of that strategy so soon after its disastrous effects is unlikely. What options that leaves is unclear.

What is clear is that capitalism has always been a crisis-prone system since its very beginnings - runs on the bank are not a new thing - and that the solution to every crisis has been to squeeze the working class until profits can be restored at an acceptable rate. In response, we can only say that we’re not all in this together. During the ‘boom’, there were no politicians, bankers and business leaders lining up to insist we all share the wealth, and in the bust we should reciprocate. Their system, their problem.

The only way to impose our needs is to stand up for ourselves – widespread strike action will make them think twice about the cuts, and in the face of industrial action they may well decide to shoulder more of the costs of the crisis. Certainly if we let them get their way, we will be paying for it for years to come, while their profits, bonuses and pensions have already returned to multi-million pound levels.

About Catalyst

Catalyst is the quarterly freesheet of the Solidarity Federation. If you want to get hold of a copy, get in touch with your nearest SolFed local, or email catalyst@solfed.org.uk. If you would like to distribute Catalyst, please get in touch with the Catalyst collective.